When the Tibetan king Trisong Detsen (r.755-794 CE) sought to establish the first Buddhist monastery in Tibet at Samye he was confronted by a problem. Whatever construction took place during the day was undone at night by the local spirits and gods who resided in the surrounding landscape. Advising the king in the construction of this monastery was an Indian Buddhist monk, Śāntarakṣita.

Although Śāntarakṣitawas learned in the study of the scriptures he was not a master of the tantric rituals required to subdue hostile spirits. He therefore suggested to the king that he invite a master known as Padmasambhava (Lotus Born Guru) who was then residing in a cave in Nepal. Padmasambhava accepted the invitation and upon arriving at Samye he performed the necessary rituals to subjugate the local spirits.

According to legend Padmasambhava was born from the bud of a lotus flower. He was discovered by King Indrabodhi who ruled the north Indian kingdom of Oḍḍiyāna. Indrabodhi took the child as his own son and raised him to become a prince of his kingdom. Already aware from a young age that the life of royalty would not allow him to benefit living beings, Padmasambhava turned to performing tantric rituals. It was during one of these rituals that he accidentally killed the son of a minister and was henceforth banished from Oḍḍiyāna. Free to follow a life dedicated to the Buddhist Dharma, Padmasambhava then travelled through various regions of India, practicing tantra in cremation grounds and meditating in caves before being invited to Tibet by Trisong Detsen’s emissaries.

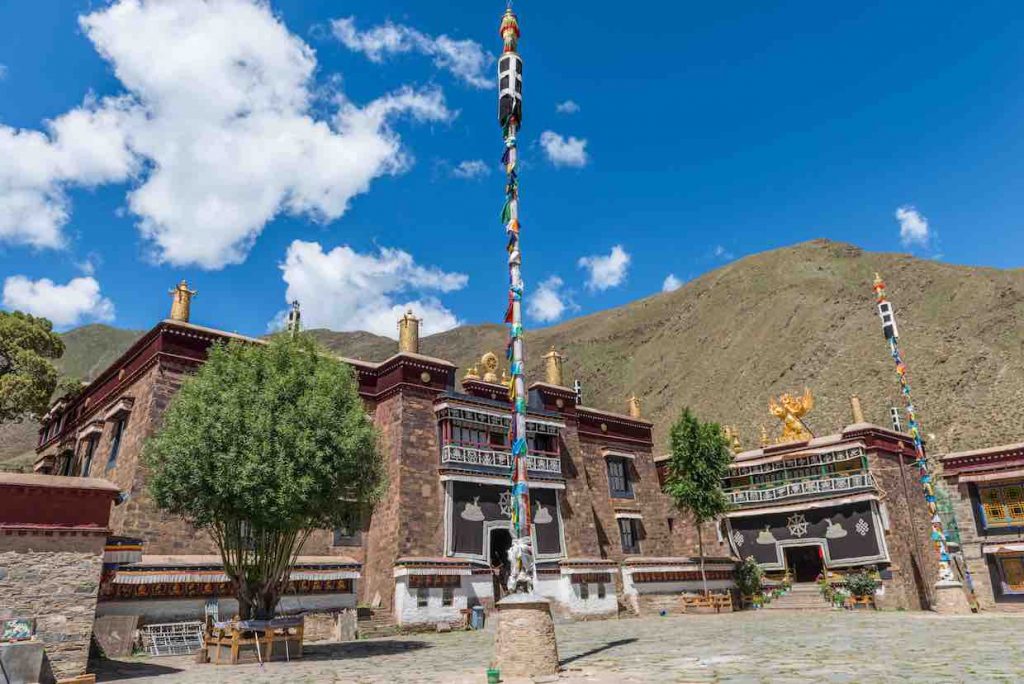

Given the rituals with which he is traditionally associated with, Padmasambhava is considered to have been a master of Mahāyoga tantras. Since he was not a monk and therefore not bound by vows of celibacy, Padmasambhava took consorts to assist him in his performance of rituals. Among such consorts the two most famous include Mandarava, an Indian princess who was considered to be the manifestation of the female Buddha Paṇḍāravāsinī and Yeshe Tsogyel, a Tibetan queen who was considered to be the manifestation of a ḍākinī. During his time in Tibet Padmasambhava also took on twenty-five disciples to whom he passed on his teachings. Many of these are known for the siddhis or magical powers they attained such as the ability to fly or pass through solid rock. An iconographical set of these deities can be seen in the Nyingma monastery of Mindroling.

As well as converting the spirits which resided within the landscape, Padmasambhava is also associated with the discovery and protection of beyul or hidden valleys. These secret locations are places where his followers could find refuge during times of persecution and where his hidden teachings could be revealed. Throughout the Himalayan region there are numerous mountain valleys which are said to contain doorways to these sacred lands.

Finally, after having established Tibet as a land where the Buddhist Dharma would flourish, Padmasambhava departed Tibet. Some traditions say that since he achieved immortality he has remained in this world where he continues to propagate the Buddhist Dharma. Others say that he resides in a palace in his pure land of Zangdok Palri (Copper Coloured Mountain).

The monastery which he assisted in its foundation, Samye, remained a centre of Buddhism in Tibet until the persecution of Buddhist monasticism by King Langdarma in the 9thcentury. Although monasticism was forced to retreat to the outer regions of Tibet, the tantric Buddhism of Padmasambhava continued to be practiced by lay adherents. It wasn’t until the 10thcentury that monasticism was eventually able to return to Central Tibet and Samye monastery was reopened.

The following period saw a rapid growth in the number of new monasteries being established and Buddhist texts being translated from their Sanskrit original. A result of this was the development of new schools of Buddhism such as the Kagyu, Kadam and Sakya. Meanwhile those who followed the older traditions came to be known as the Nyingmapa.

During this time, as the Nyingma tradition began to develop its own identity in contrast to the new traditions that were emerging, Padmasambhava’s prominence grew and his place in the mythological history of Tibet was solidified. He came to known as Guru Rinpoche and was considered to be a manifestation of Amitābha, the Buddha of Infinite Light. Aspects of his life, the legendary battles in which he managed to convert the local gods and goddesses of Tibet to Buddhism and his teachings were chronicled in biographies and terma (treasure texts) which were said to have been hidden by the master himself. These texts were revealed only to those practitioners who had a spiritual connection with the master.

Yet it is not only the Nyingma tradition which reveres Padmasambhava and his iconography can often be found in monasteries belonging to other traditions. His worship has even extended to followers of the Gelug tradition, despite their adherence to teachings which differ from those commonly found in the Nyingma curriculum. This is in part due to the Great Fifth Dalai Lama’s eclectic approach to the various traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. As a result, some Nyingmapa masters who were contemporaries of the Sixth Dalai Lama considered the Sixth to be a manifestation of the Padmasambhava. Because the Panchen Lamas of Tashilhunpo monastery are considered to be manifestations of Amitābha, Padmasambhava has also been included in the lineage of these masters.

Even for those unfamiliar with Tibetan Buddhism, Padmasambhava is easily recognisable due to his unique appearance. In contrast to monastic figures he is portrayed with the accruements that are typical of a non-monastic siddha or yogi. As such, his hair is long and he is adorned with necklaces and earrings. He wears a lotus hat, a present which was gifted to him by the king of Zahor. He is often shown as holding a vajra in one hand, while in the other he holds a skull bowl filled with nectar. Resting against his shoulder is a khaṭvāṅga, the traditional staff of an Indian mendicant. He may also be depicted in one of his eight manifestations which he took to impart teachings and perform his rituals of subjugation.

Today the teachings and the legends of Padmasambhava continue to play an important role in Tibetan culture. His mantra, Om Ah Hum Vajra Guru Padma Siddhi Hum, can even be heard in modern Tibetan popular music.