Tradition tells that during the life of the historical Buddha, Sakyamuni, a young Brahmin boy made an offering to him of a crystal rosary. For this, the Buddha blessed him and prophesised that he would one day be reborn in Tibet where he would assist in spreading the Buddha’s teachings. In order to aid the boy’s future rebirth, the Buddha ordered one of his followers, the Arhat, Maudgalyayana, to travel to Drogri mountain and bury a sacred conch which had been given to the Buddha by Anavatapta, the King of the Nagas.

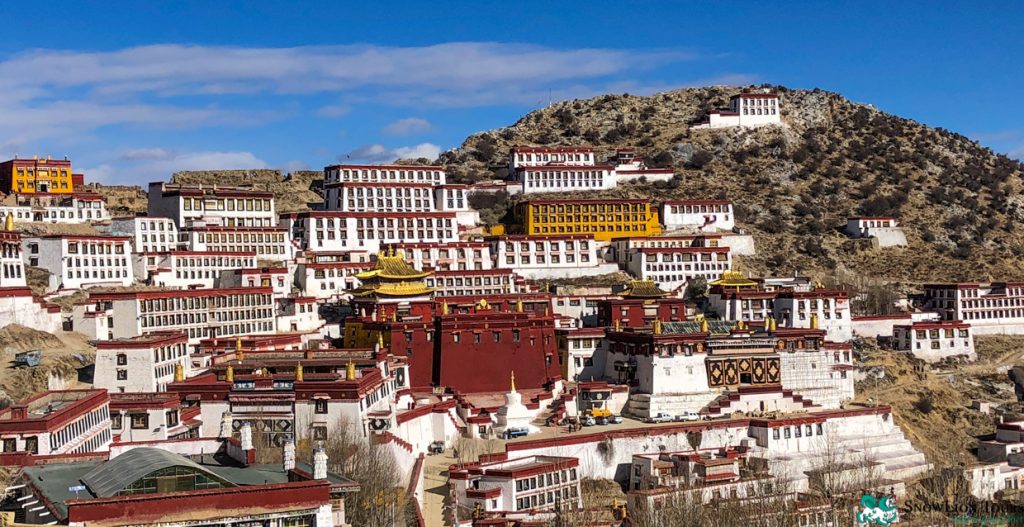

Nestled atop a ridge on Drogri mountain is Ganden monastery.

Centuries later, this conch was said to have been unearthed on the slopes of Drogri mountain by a Tibetan teacher, Je Tsongkhapa. It was there that his followers built him a monastery so that he would not be forced to travel long distances in order to perform the Monlam Chenmo prayer festival in nearby Lhasa. Sanctifying it with the name Ganden, the Tibetan form for Tushita, the heaven where the future Buddha, Maitreya, is residing, the monks who inhabited it originally called themselves Gandenpa.

The main statue in the Ganden Monastery in Lhaa

As the disciples of Tsongkhapa codified his teachings and began to form new monasteries following his death in 1419, the Gandenpa soon took on a new name in order to differentiate themselves from other traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. They called themselves the Gelugpa, the Virtuous Ones.

Tsongkhapa was born in 1357 in Tsongkha, a valley in the Amdo region of Qinghai. Initially he received the name Kunga Nyingpo from the Fourth Karmapa Rolpai Dorje (1340-1383), with whom he made his novice vows. Upon his ordination he received the name Lobsang Drakpa from a Kadampa lama, Choje Dondrub Rinchen. At age sixteen, after completing his studies with Choje Dondrub Rinchen, Tsongkhapa left Amdo for the U-Tsang region of Central Tibet.

There he studied under a variety of masters from the different traditions of Tibetan Buddhism. During this time, he was largely influenced by the works of the Indian scholar, Atiśa, whose teachings had been continued by the Kadam tradition. Studying at Sakya, he also fell under the tutelage of the renowned Sakya teacher, Rendawa Zhonnu Lodro (1349-1412). It was Rendawa’s teachings which steered Tsongkhapa towards formulating his own interpretation of the Prasangika Madhyamaka philosophy.

Having trained in the scholastic traditions of the Kadam and Sakya traditions, Tsongkhapa soon began to write his own commentaries on the subject of Madhyamaka. Concerned that he had not truly penetrated the understanding of emptiness, as taught by Prasangika Madhyamaka, Tsongkhapa entered into communication with the Bodhisattva of Wisdom, Manjuśri with the assistance of a Kagyupa lama, Umapa Pawo Dorje. Yet it wasn’t until 1398 that he achieved a full insight into Madhyamaka, after receiving a vision of the Indian teachers of this philosophy. In 1402 he wrote Lamrim Chenmo, which has since been considered one of his seminal works.

As well as a concern for clarifying the final interpretation of Prasangika Madhyamaka, Tsongkhapa reinforced a strong emphasis on adherence to the monastic code, the vinaya, and the vow of celibacy. For him, these were the necessary requirements to be undertaken before a monk could progress to the study and performance of tantra.

Tsongkhapa’s clarification of Tibetan monasticism and scholasticism attracted many followers. After his death in 1419, his disciples continued to spread his teachings throughout the U region of Central Tibet. New monasteries, such as Sera and Drepung, were founded and together with Ganden they came to form the core institutions of the newly emerged Gelug tradition. Eventually Gelug monasteries were established in Tsang, Kham and Amdo.

Tsongkhapa’s statue in Shachung Monastery in Amdo Tibet

As the Gelug tradition developed and took hold, Tsongkhapa came to be revered as an emanation of Manjuśri. Although he originally had many disciples, over time Khedrup Je Gelek Pelzang (1385-1438) and Gyeltsab Je Darma Rinchen (1364-1432) came to be considered his primary students. Today, in depictions of Tsongkhapa, you will always see him accompanied by them.

In the centuries following Tsongkhapa’s death, the popularity of the Gelug teachings led to the tradition coming into conflict with other schools of Tibetan Buddhism and their secular allies. The Gelugpa eventually sought assistance from various groups of Mongols, with whom their teachings had become popular through the efforts of the Third Dalai Lama, Sonam Gyatso (1543-1588). Yet it wasn’t until the reign of the Fifth Dalai Lama, Ngawang Lobsang Gyatso (1617-1682), that the Gelug became the dominant tradition.

The tradition spread beyond the borders of Tibet, and became the dominant tradition of Buddhism for the Mongols, including the Kalmyks who migrated to European Russia in the seventeenth century. Through the efforts of Mongol missionaries, it also spread to the Buryats of Siberia.

It was Tsongkhapa’s homeland, Amdo, which was to become the stronghold of the Gelug, and there it founded many important monasteries, including Kumbum Jampa Ling. This monastery was founded in 1560 and developed from a shrine dedicated to the spot where blood from Tsongkhapa’s umbilical cord was said to have fallen to the ground. Other influential Gelug monasteries in the region include Gonlung and Labrang.

Kumbum Monastery, the birthplace of Je Tsongkhapa in Amdo Tibet

Because of the importance it places on scholasticism, a structured curriculum supported by debate became a core feature of the Gelug tradition. Traditionally, monks from the various regions where the Gelug tradition had spread would travel to Lhasa in order to study at one of the three seats, Ganden, Drepung and Sera. After completing a rigorous and lengthy course of study, these monks were then able to receive the academic title of geshe.

When you visit Sera monastery today, you can still witness these debates taking place, showing that the teachings of Tsongkhapa still continue to play a central role within Tibetan culture.